Today probably more than ever, the division between drum pocket and drum shredding has become quite a point of discussion and display. An entire generation of players have attained a level of technical ability, blazing speed, and consumption of available space in musical time that leaves many drummers from the time before MIDI in the dust.

But in 1981, Casey Scheuerell’s drumming on Chaka Khan’s “And The Melody Still Lingers On (Night In Tunisia)” laid down a pocket that made all the chops in the world irrelevant. If you’ve not heard this song, well, you need to, because the drumming lesson within its measures will cure you of the urge to blaze and make you want to ride the whitecap of a wave that pocket drummers should strive to emulate.

I found an excellent blog post quite by accident the other night that covers the song’s history, and you can check it out here: https://movingtheriver.com/2015/05/04/story-of-a-song-chaka-khans-and-the-melody-still-lingers-on/

I can really only add a few personal comments, because this post nails what you need to know. What I love about Casey’s playing on this track is how with almost every hit, he was leaning about as far forward into the groove as he could without rushing it. That in itself in an art. So, I’m going to break the song down into the sections I could identify and share my appreciation for the groove he laid down (according to the post) in one take. Casey joined Abe Laboriel here on bass, Paulinho DaCosta on percussion, and David Foster and Ronnie Foster on keyboards.

The unmistakable essence of the melody is stated on trumpet from the start over a synth intro, and that horn is played by none other than Dizzy Gillespie, the bebop legend who composed the original tune in 1942 that this version draws inspiration from. Chaka Khan covered the hit with producer Arif Mardin, and her instantly recognizable rubato phrasing graces the first :32 seconds of the classic, followed by Casey’s single-headed tom lead-in that sets the pure pocket pace.

From that sound forward through the melody, he is on the edge of the beat, with a punchy kick that thumps you square in the sternum. The dynamic levels of snare, kick, and hi-hat find their respective places from loudest to softest, they don’t deviate from their interrelationship one bit. If you listen very carefully to Casey’s kick drum, you can hear the slightest and precisest dynamic level shift from pickup note to down beat in a two-beat pulse that rides like an elliptical cam in its delivery. Thump-THUMP, Thump-THUMP, Thump-THUMP.

Perfectly.

And when it comes time to play a two-note pattern starting on the beat leading into the bridge, each 16th note is equal in its dynamic level: THUMP-THUMP, THUMP-THUMP, THUMP-THUMP. The intentional and deliberate placement of these notes is a reflection of musical intelligence aiming exactly for the right place to put something. There’s no auto-pilot going on here. It’s a pilot flying the plane by hand every second of the song.

Casey’s fills compliment musical space the same way. They flow unobtrusively out of his hands, leaving precise room between each note, with narry a hint of hurry to get to the next one. He’s THERE. Right, where, he, needs, to, be…

Listen to the tom roll come out of nowhere at 1:45 in the song. It rise up like a swelling wave and delivers the only thing even close to fast hands. But they aren’t obliterating time and space with everything they’re capable of. They are contributing musically, like any other respectable and responsible melodic phrase.

From 1:41 to 2:55, Herbie Hancock contributes his Clavitar Keytar improv over the seamless rhythm section flow. At 2:16, Casey creates a brief floating moment with percussionist Paulinho DaCosto between two toms and the kick drum that is classic early 80s, with spacing that lets each tom hit and two-note kick phrase breathe and propel, like water drops. Again, he’s THERE… Right, where, he, needs, to, be… then back to the punctuating pocket.

From 3:15 to 3:46, the accents lead up to Chaka Khan unleashing her highest notes that go vertical and take you along for the climax ride. Then, at 3:47, producer Arif Mardin inserted a segment of the actual classic Charlie Parker’s alto sax run from the original recording, and it’s worth waiting the entire song for.

Dizzy Gillespie’s unmistakable one-of-a-kind trumpet voice restates the melody and improvises the song out to the end over Chaka’s haunting refrain, guiding the musical ghost back into the night from which it came. According to the above-referenced blog post, Gillespie almost wasn’t able to make the session. Doing so bridged a 40-year musical gap that no one else could have done, and seriously, it should give you the chills it deserves.

Nothing is going to stop the onslaught of all too often unmusical obliterating drum set overkill from its social media driven proliferation, but for 5:00 minutes in 1981, there was none of that to be found. There was only masterful pocket and musical excellence, revisiting and respecting a timeless classic that bridged that fused jazz and pop music in a very unique way. A tip of the hat, so to speak, to days gone by when musicans reached into their creative unknown, exploring a new style of jazz that begged for the dogs to be let off the leash to see how fast, far, and intensely they could run. With Chaka Khan’s “And The Melody Still Lingers On (Night In Tunisia),” drummers have a model of how to propel and support, thanks to the tasteful contribution of Casey Scheuerell. So crank this song and hit replay, and hear how your job as a drummer and a musician should be done. Right, there..

/ /

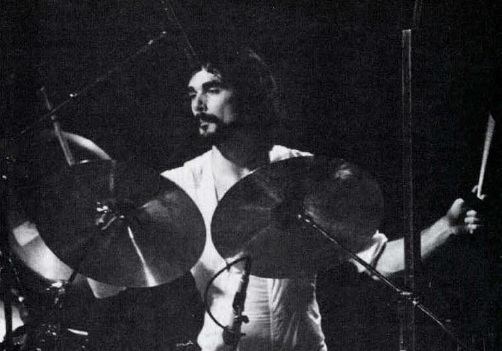

Casey Scheuerell is known for his work with Gino Vanelli and Jean-Luc Ponty, and he’s the author of Stickings and Orchestrations for Drum Set (Berklee Press), as well as Berklee Jazz Drums (Berklee Press), which by the way, you might have seen a copy of the recent season of Fargo. Actress Sienna King, playing daughter Scotty Lyon, is seen holding a copy of the book at the dinner table.

Casey is a Professor of Percussion at Berklee, where has taught since 1993. His website is http://www.caseyscheuerell.com, and he probably doesn’t remember, but I sold him records once at Big Ben’s in Encino, California, way back in the day…